Chess Set

MANAS, THE KYRGYZ & THE GREAT SILK ROAD: A sojourn into the small world of folk-art chess pieces in Central Asia

[The suffix, –stan is from Old Persian, also -istan or -ustan, meaning ‘land of’ or ‘a place where there are many of.’ Kyrgyz is pronounced krrr–Giz with a rolling ‘Scottish’ r and emphasized g. Manas is not pronounced ‘manners’ but m’Naz with a lingering zzz and emphasis on the n. You’re all caught up.]

To be quite honest, just a few months ago I’d never even heard of the Kyrgyz people, or their ancient leader, the Great Manas, or for that matter Kyrgyzstan itself. So the following observations are the fruit of fresh research intermingled along the way with a fair-to-middling knowledge of our game’s history and a lick of Old World history to boot. In regards to finger-on-the-pulse events, I’m not too shabby there either, for as you’ll no doubt be aware, the first Friday of the month (March 5th) marked the worldwide celebration of National Ak-Kalpak Day! National ‘Who?’ Day, I hear you hoot. Well, it’s not exactly a ‘who’ but rather a ‘what?’ In short, the kalpak (a cap or hat) is the traditional white felt headwear of the old Kyrgyz tribesmen, championed only recently as a symbol of the country’s cultural and national identity in order to restore “a sense of patriotism and pride” (to quote a government line) amongst the country’s three million or so largely nomadic inhabitants – a fine example of which can be seen here in PIC1 (below) enthusiastically modelled by a village elder.

The ‘status’ of this gentleman we can readily establish from the height of his ‘titfer’ (tit-for-tat = ‘hat’ in my old Londunistan rhyming slang) because throughout Kyrgyzstan, ‘the taller the titfer, the higher you sit, sir’ in the hierarchy of Kyrgyz tribal life, as we shall further explore, for I was only made aware of these quaint, archaic customs through the recent purchase and restoration of a rustically charming, hand-painted Kyrgyz chess set.

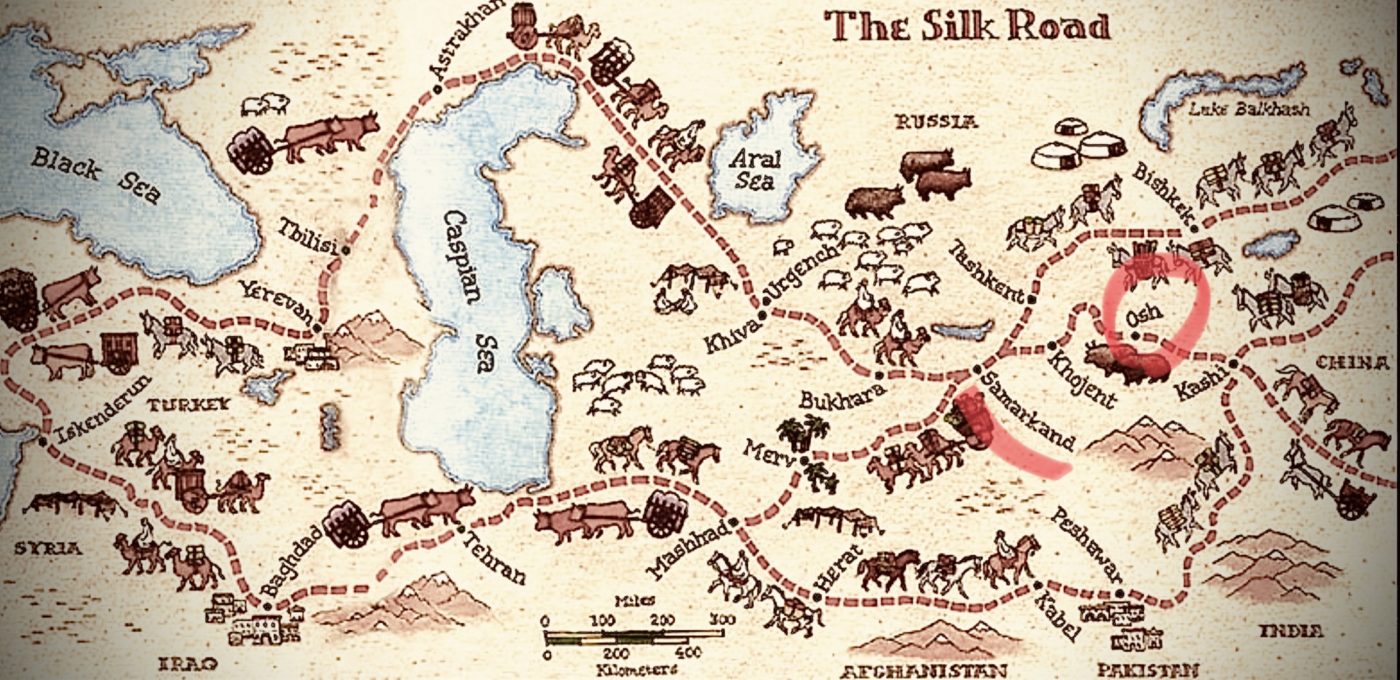

But before we dive into this month’s chessay let’s first get our bearings, for perhaps, like in my case, you may be a little unsure as to where modern Kyrgyzstan is situated exactly. As you can see in PIC2 (right) the old Kyrgyz tribes lived in a landlocked, mountain-encircled region surrounded by some powerful and mainly hostile neighbours (to say the least).

In fact, the territory was ruled at one time or another by all of these merciless invaders, most notably, in the sixth century by the Tang Dynasty of China, the Turkic tribes from modern Uzbekistan/Turkmenistan to the west (c.9th century), Genghis Khan’s infamous Mongols to the east (13th century), the Muslim Uzbek Khanate once again in the early 1800s and finally by Imperial Russia in 1876. Quite understandably, over the centuries these various invading forces had a massive cultural impact on the Kyrgyz people, especially in regards to their traditional dress, religious beliefs, weaponry and armour and their nomadic lifestyle in general. The latter of which included a penchant for the occasional game of shatranj (an earlier form of chess), which had invaded Central Asia from Hindustan (modern India) via the Great Silk Road sometime around the seventh century, possibly earlier. We can say this with real certainty due to the Samarkand ‘ivory’ chess pieces (c.650-750), “chess pieces referred to in tales about the invention of the game” (Linde; Soviet Life, 1980) unearthed in modern-day Uzbekistan by the Soviet archaeologist, Dr. Yuri Buryakov in 1977 which remain, to date, the earliest authenticated chess pieces yet discovered (for a closer examination of Buryakov’s find see Linde, The Art of Chess Pieces, Moscow 1994, pp. 58-63 or just Google “Samarkand chess pieces” for visuals).

Like the scholarly and ancient city of Samarkand to the west, the sprawling market town of Osh (PIC3, above) in southern Kyrgyzstan – still a noisy and colourful bazaar today – was a most welcome sight for the mish-mash of merchants, diplomats, mercenaries, pilgrims, artisans, fortune-seekers and tricksters et al that had bravely traversed the Great Silk Road since at least the third century.

Accompanying these droves of travellers, or the caravansaria as they were then known, came the much sought-after silks from China, spices, dyes and ivory from India, along with various precious metals and stones, exotic animals and birds of every description, not forgetting the prized ‘cure-all’ opium potions so popular with the apothecaries of the West. Granted, these were all luxury goods, as space was very precious on the backs and carts of the sure-footed oxen, donkeys and camels that navigated the dangerous trails of the Great Silk Road. But in large encampments like Osh, where the caravansaria could lodge for a night or two, there was plenty of time for cordial interaction between traders, travellers and the locals alike. No doubt, there was much merriment to be had after many weeks traipsing through deserts and navigating hazardous mountain trails; stories, jokes and traditional songs could be swapped over a strong beverage, women were courted, dancers danced and wagers were laid over cockfights, arm-wrestling and drinking competitions. For the more esoterically minded, variants of games such as shatranj, nard (backgammon) and alnurd (dice) could be played and also taught to interested locals along the route; games that pilgrims, ambassadors and hustlers would have brought with them from their homelands; games that through the melting pot of Osh would eventually wind their way into Russia and Persia onto what we now know as the European Continent and ultimately into all of our homes today.

This is the history that I absolutely adore about chess. When restoring a vintage hand-painted set you are walking in some other artist’s footsteps, imbibing and exploring their culture, comprehending their ideas, their choice of techniques and palette, assessing their skills and their flaws. In a way, it’s very much like the game of chess itself. The more you study a certain piece (or position) the more you see. Oftentimes during the course of a game, my mind tends to wander: ‘The rooks are quite unusual – why are they shaped this way?’ ‘That looks very much like traditional clothing on the King. Is this a regional thing, and if so, what region?’ “Why is the queen smothered in asterisks? Needless to say, I don’t win many games, but questions such these as are what first attracted me to the aforementioned “Soviet artisanal set” (seller’s words) that at first glance resembled the traditional Russian Matryoshka or ‘nesting doll’ chess pieces, but these pieces were different, much more artistic, more detail-oriented. The set was up for sale online but in a pitiful state, as the pieces were smattered finial-to-foot in small, dark blotches. A rare condition, I explained to my curious wife, known in restoration circles as the blue-bonic plague! PIC4 (below left) Taking this damage into account they were reasonably priced, so I took a gamble and picked them up, hoping I’d be able to cure the poor lepers of this unsightly malady – “you’re not bringing that plague into this house are you?” commented wifey, “We’ve got enough diseases floating around the planet already, thank you!” Nevertheless, the patients were en route …

Once in hand, the ‘blue-velvet’ eyesores were carefully teased away from the surface using soft cotton swabs, a splash of methyl-hydrate and a generous dollop of patience as care had to be taken not to remove the intricate ink-work below. PIC5 (above right – Clean Queenie!) The process was a lengthy one, but it was during this slow, repetitive procedure that I began to truly appreciate the deft artistry involved in the twirling, swirling, vine-like patterns that seemed to float, almost ethereally, over these shapely wooden figurines (I blame this ‘moment’ on the meth fumes!). But seriously, who were these elaborately dressed characters? Who did they represent, indeed, if anyone at all?

They resembled Mongol warriors, PIC6 (left) but the seller specifically referred to them as “Russian” and “Soviet” (ruling out Genghis Khan) so at this point I was slightly befuddled. I revisited the listing details and realized I had overlooked two good leads; the unusual term “Kirgiz Chess” (huh?) and the equally baffling “Manas chess set from Kirgiztan” – admittedly, all gobbledygook to me in January of this year, but we live to learn.

A quick search for ‘Manas’ quickly threw back a porno site from Latin America and a bunch of hair-dye and make-up products for middle-aged men! Hmm. I punched in “Kirgiztan” and instantly got a bunch of spell-check hits for the consonant-heavy republic of Kyrgyzstan. Huzzah! Much more promising – but where the Hell was that? Pulling up a map I see that it’s one of the smaller states in the colloquially known ‘Stans’ of Central Asia (quite close to Mongolia) that gained its independence from the Soviet Union shortly after the iron curtain fell in 1991. The set was dated to the late ’70s, so for the seller to call it ‘Soviet’ and ‘Kirgiz’ suddenly made perfect sense. Now I had the pen between my teeth! I punched in ‘Kyrgyzstan + Manas’ and a whole new world opened up before my very eyes.

It is nigh impossible to delve into the history of the Kyrgyz people without stumbling across the legend of the great warrior-god, Manas. There is virtually no written history on the nomadic ancestors of the Kyrgyz people other than that of their enemies who describe them as something akin to ‘rats.’ For a clearer insight into their roots, national identity and ancient customs, modern historians glean what facts they can from a truly gigantic folklore poem that has been orally passed down from one generation of Kyrgyz to the next for (some say) countless centuries. For a mainly uneducated people it served (and still does) as a sort of verbal link to their ancestors, schooling the listener (usually at religious ceremonies and festivals) on subjects like philosophy, history, the spirit world and integration, but for the main part it’s a basic ‘how-to’ guide on living a “brave” (men) and “creative” (women) existence following the example (of course) of their national hero whose birth, coming-of-age, conquests and death are celebrated and mourned over the course of the aptly titled Epic of Manas. This colossal work that is purportedly over 1000 years old was composed in the form of a trilogy covering three generations: the god-like Khan Manas, his first-born, Semetei and his grandson, Seitek – all of whom now have a chess set named after them!

Incredibly, this massive poem is memorized in its entirety by the shamanesque manaschis (‘chanters of Manas’) PIC7 (right) and according to The Guinness Book of World Records weighs in at a whopping 500,553 lines in length, over 20x the size of Homer’s Odyssey (!) and can only be performed in full using ‘tag’ teams of manaschis chanting around the clock for “three days and three nights” – don’t think I’d be down for the long-haul at that party!

Harking back to what I said earlier, regarding ‘the Kyrgyz had a penchant for shatranj,’ you may well have wondered how I arrived at this assumption. Well, after a great deal of digging (believe me!), the answer to this question was eventually unearthed in the Epic of Manas itself. Because from a very young age the Kyrgyz school their children to behave and act just like their great leader, Manas, and in the first book of the epic that leader and his entourage spend a pleasant morning out hunting, drinking and playing at shatranj and other games;

They had killed a yearling to the south And a mare to the north,

They had been devouring the kazi1Kazi: a sausage made from horsemeat and fat. It’s a delicacy and the most expensive sausage in Central Asia today. Amongst the nomadic tribes it’s customary to make these sausages (from the rib meat) immediately after a horse is slaughtered.

And gulping back arak2 Arak: a strong distilled spirit in the anise/absinthe family. in the Kalmyk way 3Kalmyk: from modern Kalmykia, direct descendants of the Mongols where chess is called shatar. way.

They had been playing chatirash4Chatirash: translator’s footnote; “Chatirash (Pers.) is a name of a game similar to chess.” Without question this is shatranj, derived from the Sanskrit, chaturanga, the prototype of chess. [shatranj] (line 7903)

And making much noise,

They were absorbed in their fun,

Playing ordo5Ordo: trad. Kyrgyz outdoor game played with horse and sheep knucklebones aimed at a pin called the “Khan” who is protected by soldiers. and other games.

[The Kyrgyz Epic; Manas, trans. Elmira Kocumkulkizi, Uni. of Washington, Seattle. 2005]

Line 7903 above is the only mention of shatranj in the few English translations that are available of the Manas. Also, of the many books I’ve glanced over on the history our game, including most of the classic works, this is the first and only time I believe (and please correct me if I’m wrong) that a concrete link between chess, the Epic of Manas and the ancient Kyrgyz tribes of Central Asia has ever been unearthed. In that respect, it could be useful in determining when (roughly) the Epic of Manas was composed, as learned opinions range from the late tenth century right up to the nineteenth century. It also underlines a longstanding history between the nomadic tribes of Central Asia and the game of shatranj, or as the Kyrgyz knew it, chatirash.

But that is another story, on with our chessay!

THE SHAMAN

Without going into mind-numbing detail, the mythical life of Khan Manas, and all the ‘Romanticism’ that rides along with him, most closely resembles (in my mind) the well-known western legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, intertwined, perhaps, with the epic poems of heroism and bravery found in the chansons de geste (‘chants/songs of deeds’), sung not by manaschis, but by their European counterparts, the jongleurs e trovadors, (‘minstrels and troubadours’) of southern France and Spain. The chansons de geste date from the tenth century on, dealing mainly with the victories of Charlemagne of the Franks, and in Aragon, Alfonso the Battler, but unlike Arthur and Manas, there was never a doubt over King Charlemagne or Alfonso’s historicity. Whether or not Manas and Arthur truly existed (and I doubt it) is certainly not a matter for this chessay, but the trade routes over land and sea linking the Mediterranean traders to those of the Far East certainly did.

We know shatranj entered southern Spain during the eighth century sometime after the Moorish invasion of 711, and by the late 1200s had spread throughout the country. This is confirmed by King Alfonso the Wise of Castile’s famous Illuminated MS, A Book of Chess, Dice and Backgammon (Seville 1283) which shows scenes of Arabs and Christians sitting down together conversing, swapping stories and playing chess. PICS 8&9 (below)

My point is, it wasn’t only luxury goods that were being transported back and forth between the two continents, but also cultural ‘goodies’ like art, music and parlour games, such as chess and backgammon. Chansons, poemes and rimes must also have been traded, telling of famous kings, khans and shahs and their victories over uprisings and usurpations, of gallant knights, chivalry and heroic deeds – and let’s not forget – in mediaeval times this was the hot gossip and entertainment of the day in any court of the world!

These tales of the exotic Orient and Arabia were extremely popular in medieval Europe and visa-versa. For centuries to come stories would still be traded back and forth, just one prime example being Antoine Galland’s classic tale of Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves (made famous by the Frenchman who overheard the original story from an Arabian ‘master of the verbal arts’ visiting Paris during the 18th century). So it is quite feasible that versions of the Arthurian tale may have been told as far afield as Central Asia, too, certainly by the 15th century when the first extant ‘recorded’ reference to Manas appears in the Persian MS, Mojmal al-Tawarikh (A Collection of Tales). The first ‘recorded’ account of King Arthur (that brought with it “international interest”) is in the pseudo-historian Geoffrey of Monmouth’s fanciful chronicle, De Gestis Britonum (On the Deeds of Britons), stories from which were widely circulated from the early twelfth century on. So it is also likely that trovadors and manaschis, having ‘overheard’ these wondrous tales from travellers and fellow ‘wandering minstrels’ may have also inadvertently intertwined the two folk tales, as a large part of being a successful and entertaining chanter was the deft skill of ‘improvisation’ – the art of sprinkling fresh spice over an old yarn, you might say, much like what the Sex Pistols did to Sinatra’s My Way, should you need a modern comparison.

On the subject of comparisons, there are two in particular that catch the eye when comparing these legendary tales from east and west. We are all aware of the story of Excalibur, the magical sword that was lodged in a rock and could only be removed by the rightful king of the land. Well, not to be outdone, Manas also wields a sword, but his is called Achal-bar (admittedly, the name does vary in other versions of the epic) and whether by coincidence or not, Achal is actually an ancient Sanskrit term for “the immovable one.” I kid you not! But returning to our chess theme – as mentioned, my mind is nomadic – it is also well known that Arthur was raised under the guidance of a wise and wizened old sage, the cave-dwelling sorcerer we all know as Merlyn. Again, not to be outdone, Manas was also raised by a mystic of sorts, reputedly “born unto the mountains,” a shaman or “wise man” by the name of Bakai, that scholars of the Manas call the khan’s “trusted teacher” and “spiritual advisor” who could ‘see’ trouble brewing from a mile off – could this shaman, Bakai, be our bishop in the Manas chess set, hovering on the shoulder of his king and queen should they ever need advice? If I were a betting man I’d bet my wife on it!

If we examine the piece closely PIC10 (above left) we can tell by his attire that he’s a figure of some importance. The piece stands at 12cm and sports a tall, decorated warriors helmet in the style of the Turkmen (something similar to PIC11, above right, perhaps) and is cloaked in a traditional Kyrgyz felt robe or deel embroidered with expensive silk lace. He wears a full beard that is painted white on the darker pieces signifying age and wisdom and around his waist is a broad Turkic-style belt, or kemer, trimmed with precious stones attached to a massive jewel-studded buckle – an elevated version of the one worn by the manaschi (who are also linked to Shamanism) in PIC 7. Quite fittingly, in the fountain gardens of the National Philharmonic Building, the “home of folk poetry and music” in the Kyrgyzstan capital of Bishkek (renamed ‘Frunze’ by the Soviets after a friend of Lenin) there stands a cast iron statue of a long-bearded man overlooking four granite busts immortalizing four of the most popular Kyrgyz manaschis of the past. The statue is of the shaman, Bakai, PICS 12&13&14 (below) humbly dressed in a plain deel and tall kalpak. He stares down at the observer with his large “all-seeing” eyes as if he is peering into their soul …

[If you have a spare 20 minutes in your life here’s is a link to a short Kyrgyz film, Manaschi, shot in 1965 capturing a performance by one of the last old-school masters of the verbal arts, Sayakbay Karalaev, the “Kyrgyz Homer” (d.1971). The recital wouldn’t have changed much from one given in 1865, or for that matter 1565. Warning: There are some grizzly scenes of the 1917 uprising involving hangings.]

In part two we will continue to explore the Epic of Manas and put some more names to faces as well as showcasing several sets from ‘The Stans’ region of Central Asia.

Until next time, check you later!

Info Sources:

www.silkroadfoundation.org The Kyrgyz Epic; Manas, trans. Elmira

Kocumkulkizi, Uni. of Washington, Seattle. 2005

Wikipedia.com

The Silk Road: A New History, V. Hansen, Oxford Uni. Press 2012

A History of Chess; Golombek, London 1976

A History of Chess; Murray, Oxford 1913

The O.C.C., Hooper & Whyld, Oxford 1996

Photo Credits:

Header; National Geographic Traveller, Nov 2005 credit: Stephen Lioy

Pic 1,2,3,7,12,15; Wikipedia

Pic 5; A.Chelnokov (Etsy store; ChessHarbour)

Pic 8; Chess in Art, Raabenstein, HereLove 2020

Pic 9; Met. Mus. of Art @ livescience.com

Pic 13 & 14: anon. Kyrgyzstan tourist

Pic; 5,6 & 10: authors

All photos have been reworked and edited.

If you have any problems with them featuring in this article please let me know

@ thechessschach@gmail.com

All rights reserved: Alan W. Power (The Chess Schach), March 2021